Best known as a Pop artist, Andy Warhol was initially a successful commercial illustrator. This experience provided Warhol ample opportunity to hone his abilities as a draftsman, a skill he valued and continued to perfect throughout his life. The drawings he made at that time have a delicate and ornamental quality that combine vivid colors with humorous captions, paving the way for some of his later Pop Art work.

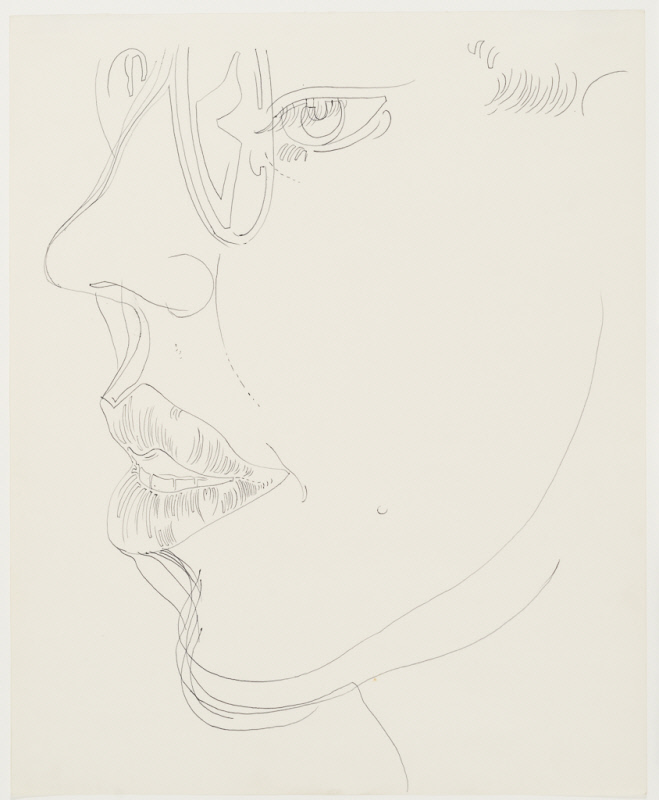

The 1962 drawings of Gene Swenson (objects 1972-34.01 DJ, 1972-34.02 DJ, 1972-34.03 DJ, 1972-34.04 DJ, 1972-34.05 DJ, 1972-34.06 DJ) reveal a quieter, more intimate side of Warhol’s practice. Seen together, the six drawings that appear to progress from a more conventional portrait to the extreme close-up can be understood as the artist’s slow familiarization with the model, a gradual moving into closeness. The soft flowing lines add to this sensuality and convey an almost palpable tension between Warhol and his model. The precision and ease of the drawn line and the meticulous capture of Gene Swenson’s features attest to Warhol’s comfort with the medium of drawing.

From 1961–65, Gene Swenson worked as the editorial assistant of ARTnews and held many interviews for the journal. This work gave him the opportunity to interact with several key figures of American art and specifically those associated with Pop Art, both professionally and socially. As an art critic he reviewed the exhibitions of Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Robert Indiana, Tom Wesselmann, as well as James Rosenquist, whose work he especially admired.

Swenson is perhaps best known for his 1963 interview of Andy Warhol in ARTnews as part of “What is Pop Art? Answers from 8 Painters, Part I” in which Warhol is quoted as saying “I want to be a machine.” This statement has been used by scholars to qualify Warhol’s persistent fascination with his industrial means of image production, his embrace of modern mass-produced objects, and his seemingly cold gaze in the face of the loss and violence in the events that inspired series such as Electric Chair, Marilyn Monroe, Race Riots, and Tuna Fish Disaster. In the late 1980s and ’90s, art historians revisited these works to acknowledge Warhol’s critical viewpoint and their inherent pathos. But it was only in 2018 that the art historian Jennifer Sichel published Swenson’s interview of Warhol as it was initially recorded. The previously unpublished parts reveal that the initial edits made in 1963 exclude the dialogue’s queer content. In its full version, the exchange between Swenson, Warhol, and others associated with the Factory playfully discloses Warhol as a gay man and suggests the statement “I want to be a machine” can also be understood as an ethic of nondiscrimination—an embrace of both sameness and difference alike—while framing Warhol’s Pop Art as a form of queer artmaking.